Practical support for identifying and meeting need

Physical and sensory

Physical, including motor co-ordination

Physical skills support all aspects of a child’s life, from self-care and schoolwork to play and developing independence.

How do physical skills develop?

Unless a person is born with a physical difference or has had an injury that has led to a physical difference, physical skills develop in a sequential manner – but they take different amounts of time to mature in each individual.

Acknowledged physical developmental milestones classically start from birth and go up to five years of age, so any significant delay should have been identified prior to a child attending full time education.

Although physical skills continue to develop after five years old, they tend to be much more dependent on experience, opportunity and motivation e.g. learning to ride a bike, tying shoe laces, sports.

Poor development in any area, or missing developmental milestones, can affect the acquisition of skills that rely on them.

Physical skills and learning

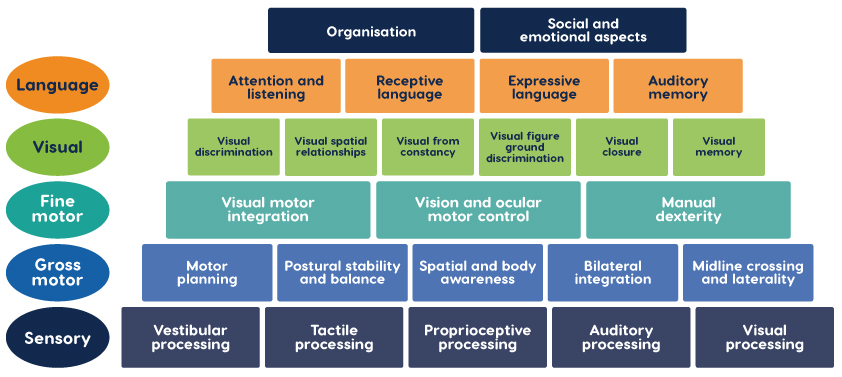

Physical skills do not develop in isolation. Development relies on a complex interaction of motor skills, sensory perception, sustained attention, having the desire to take part (social and emotional) and cognition (understanding, conceptualisation, planning, sequencing, remembering, and execution) that all support each other. This means that it is important to consider physical skills holistically, taking on board an individual child’s journey of development:

- their opportunities to learn and refine new skills

- their understanding of how to use their physical skills

- their ability to attend to an activity and

- their desire to take part.

Building block for learning – Jenkinson, Hyde and Ahmad, 2012

Click to expand

What are physical and motor co-ordination needs?

There are a range of different physical needs that can affect a child in school. These are some of the most common:

Immature physical skills as part of a general developmental delay

Children who have general learning needs may well achieve their developmental milestones at a slower rate than their peers across all learning areas, including physical skills. For example, they may continue to need help changing for PE long after their peers have mastered this skill.

The good news is that as they grow and mature, they are likely to make progress physically and develop their skills and independence without the need for specialist support. You can find some strategies for helping them with specific skills below.

Motor coordination difficulties

Coordinating movements is a complex process that involves many different nerves and supporting processes within parts of the brain. As with other areas of development, some children master this more easily and at an earlier age than others do.

It is an essential element of development because it underpins many everyday activities. A child with coordination difficulties may appear awkward and clumsy as they may bump into objects, drop things and fall over a lot.

How to spot children with motor coordination difficulties in the school setting

Here are some signs you may see in school when a child has motor coordination difficulties BUT remember that this can often be part of the bigger picture and not a specific area of concern.

Only a small number of children with physical co-ordination difficulties end up with a specific diagnosis.

Classroom activities including writing

Their handwriting and drawings may appear scribbled, lack the volume and may be less developed compared to other children their age.

Mealtimes

They may be unable to use age appropriate cutlery.

Getting washed and dressed

Needing assistance and reminders around personal hygiene, poor sequencing of clothing, clothes inside out (beyond age appropriate).

Art and craft

Difficulty with; scissors, glue stick and colouring within the line, drawings are smudged and or developmentally immature.

Sports and games

Does not have the same physical skills as peers, does not get picked for team games, cannot anticipate what is required.

General clumsiness

Bumping into people and objects, frequent falls.

Is this really due to a motor co-ordination problem?

Sometimes detective work may be needed to work out whether a child’s needs are really due to motor co-ordination difficulties.

Inter-relationships between the child’s learning ability, self-esteem, self-belief, motivation and their different abilities, skills and needs across areas of development can require careful unpicking. It is best to keep an open mind and document classroom observations.

Click below to find some useful questions to ask if a child has needs in the following areas:

Concentrating

- Do they feel uncomfortable so find it hard to sit still?

- Are they distracted by the environment?

- Have they no desire to take part in the activity having preferences for specific activities which they are good at?

Following instructions and copying information

- Are they struggling with a whole class approach?

- Would they be better seated in a different position within in the classroom? (for physical and/or sensory reasons)

- Is classroom language too complex for them to understand?

- Are they struggling with the sensory side of the classroom environment and getting distracted? (background noise, movement, visual displays etc?)

- Do they need an eye test?

Organising themselves and getting things done

- Can they physically organise their body to do the tasks?

- Are they cognitively able to conceptualise, sequence, plan, remember be able to execute an action?

- How is their self esteem? Do they believe they can succeed?

Behaving in line with expectations

- Are they frustrated?

- Are they ‘clowning around’ to distract from their difficulties?

- Are sensory issues affecting behaviour?

- Are the expectations unrealistic given their developmental level and needs?

- Are underlying emotional issues affecting behaviour?

What is developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD)?

Developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) may be diagnosed if a child has significant and ongoing challenges with motor co-ordination that cannot be explained by any other condition e.g. general learning needs, global developmental delay or specific medical condition.

For diagnosis to take place children must meet a strict criteria set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Edition Five (DSM-5).

DCD is thought to be around 3 or 4 times more common in boys than girls.

Although DCD may be suspected in the pre-school years, it’s not usually possible to make a definite diagnosis before a child is aged 5.

Most healthcare professionals use the term developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) to describe the condition, although you may also hear it referred to a Dyspraxia.

Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the name for a group of lifelong conditions that affect movement and co-ordination. It’s caused by a problem with the brain that develops before, during or soon after birth.

The severity of symptoms can vary significantly. Some people only have minor problems, while others may be severely disabled.

Once a child is identified as having cerebral palsy, their physical development will be monitored by health professionals in line with national guidance. They will be provided with any therapy or treatments that they need in order to stay as healthy, active, functional, independent and as mobile as they can be and get on with living their lives.

Individual advice for school staff on how to support them will be provided by the occupational therapist, speech and language therapist or physiotherapist when necessary.

Hypermobility

Hypermobility is a description of joint movement. Hyper means ‘more’ and mobility means ‘movement’. Ligaments offer stability to joints and in hypermobility, ligaments are lax and joints have more flexibility.

It is not an illness or a disease, just the way someone is put together. It is considered a normal condition by medical professionals.

Studies have shown that up to 71% of children under 8 and 55% of 4–14 year olds are hypermobile.

For the vast majority of children, hypermobility is not problematic. Children may have an awkward grip but be able to write within acceptable limits and manage to keep up with their peers. In fact, hypermobility is beneficial in the performance areas of ballet, some martial arts, and gymnastics. Individuals who are successful at these performance areas have very good control of their muscles around their lax joints.

As a child develops and becomes more active, hypermobile joints generally become stronger. Coordination may improve and the child should be less tired.

However, if you are concerned that hypermobility is causing real difficulties for a child including pain and or affecting function, please ask their parents to take them to the GP who can arrange for the appropriate assessments to take place with a paediatrician or rheumatologist to check for any underlying medical cause.

Red flags

If a child starts to struggle with physical skills where they previously had no difficulties, this could be a sign of an underlying illness or emerging condition. In this situation, it is important to discuss your concern with the child’s parents / carers as soon as possible and ask them to take their child to the GP.

Practical ideas and strategies

If a child needs support to learn a physical skill, it is worth considering the following:

Consistency and links with home

A discussion with parents regarding how their child is managing at home will help to paint a picture of development and opportunities outside of school.

An agreed joint approach across school staff and with parents is essential, to ensure consistency and avoid the child becoming confused or overwhelmed.

Skills which might need a joint approach from school and home are:

- General physical activities such as hopping, jumping, running, and catching or kicking a ball.

- Walking up and down stairs

- Using the toilet

- Using cutlery

- Writing, drawing and using scissors

- Getting dressed, doing up buttons and tying shoelaces

The importance of opportunity

Have opportunities to learn and practice a particular skill been limited? It is worth discussing this with parents and, if needed, creating opportunities with appropriate level of support to learn and practice. Try to record and monitor progress.

Society is always changing and the way we live our lives change too. Some skills that might once have been expected at a certain age a generation or two ago may be entirely different now. Some basic skills that start at home can be delayed due to changing social influences that reduce opportunity.

- Play at home – opportunities for small world, out door and general imaginative play, home based arts and crafts have decreased with more preference for screen based play with less direct social interaction, use of imagination and manipulation skills (construction play, pencils and crayons, scissor use).

- Changes in family eating habits – more children and families are eating finger foods sitting on sofa – with fewer opportunities to sit at a table or use cutlery. There may be no table at home to sit at to complete homework.

- Velcro fastenings – all children were once expected to be able to tie their shoe laces before starting school at 5 years old. The average age to learn is now 8 years of age when children tend to move into the larger UK size shoes of sizes 1 and 2 and the use of Velcro reduces.

Developmental readiness

- Try to work on developing new skills which are the next step on a typical developmental pathway – rather than jumping ahead to more demanding tasks

- Consider whether the child is ready to work on a particular skill given their overall level of development. For example, they may have the physical skills to get themselves dressed but not be ready from a concentration and independence point of view.

Structured skill teaching

Initially, new skills within all aspects of learning need to be taught, with appropriate scaffolding and opportunities to practice. This supports the natural development process. Physical skills are the same. Where the development of physical skills is delayed, try to:

- Target one main task at a time (skills for one task may then support others)

- Use modelling and scaffolding techniques

- Build in lots of repetition

- Differentiate tasks and the curriculum where necessary

- Record and monitor progress

Sensory needs

Have you considered the impact of sensory difference on functional and physical development? Some children can be fearful of specific physical activities e.g. jumping down from a piece of equipment.

Motivations and rewards

Consider the impact of what motivations and rewards the child seeks. Some children are more driven towards becoming independent than others. It can be useful to consider what’s in it for the child if they learn a new skill.

Check with the family if the child considers the task the adult’s job e.g. cutting up their food. Have they ever been expected to complete this task? Do they enjoy the adult attention when they get helped?

Does the child have preferences and/or obsessions for specific tasks only and does not retain the skills or processes for what the child may see as a mundane task?

What might help:

- Work jointly with families as needed

- Create expectations and rules around a task for that child

- Break down the task into achievable chunks

- Use school based rewards systems to reward effort

A functional approach

Children with needs in this area are likely to make progress but may always need some support and tasks differentiated appropriately so that physical needs are not a barrier to learning.

If a child continues to struggle with any aspect of learning despite being taught and having had access to opportunities, much more emphasis needs to be placed on coping strategies and or adapting the environment alongside differentiation where required. Practical ideas for doing this in relation to specific tasks are in the section on practical ideas and strategies.

Developing specific skills

Handwriting and pencil control

Differentiation from a school based handwriting policy

Children who struggle with basic letter recognition and letter formation, need to consolidate basic skills first and foremost. The enforcement of a cursive handwriting policy can be detrimental to some children’s ability to show learning, actually move on with their learning and on their emotional health. This can lead to a deep seated dislike of school. Differentiation in these cases is essential.

There are some effective developmentally based handwriting programmes available that are recommended by the local occupational therapy team:

Write From the Start

A perceptuo-motor programme by Lois Addy aimed at integrating vision and movements (the direction and physical feel of movements)

- Helpful where sensory (proprioception and tactile) issues are suspected

- Includes two programme books and one teacher guide

- More effective in key stage 1 but can be used in key stage 2

- Minimal cost

- Easy to follow

Speed it up

A hand writing programme by Lois Addy aimed at 8–13 year olds whose handwriting is slow, illegible and lacking in fluency.

- One book containing a base line assessment and an 8 week programme

- Programme must be given the time to be effective

- Can be completed in small groups with a variety of ages

- A double sided writing board is needed. Once got, they can be used many times

- Minimal cost – easy to follow

Lots of useful information about how best to support handwriting can be found below:

Issues to consider when supporting children who are left handed:

Alternative methods of recording

Schools can choose to implement alternative methods of recording to enable them to see what learning has taken place. This does not require an OT assessment.

- Scribes

- Voice recordings

- Laptops and tablets

- Printed worksheets where only answers are required

- Printed worksheets that reduce the need to copy from the black board

- Use of brainstorming/spider diagrams

- Providing prepared sheets with homework detailed on it

- Specialist soft wear programmes (e.g. Nessie) may be advised

- ICT – AbilityNet have good information re keyboard skills

Other useful information on alternative forms of recording can be found here:

Specialist – additional support for children and young people with an ongoing and significant identified need

Learning environment

- Specialist resources may be necessary, e.g. changing beds, toilet adaptations, hoists, walking frames/standing frames, steps, specialised seating and ramps/greater access. Occupational therapists and physiotherapists can offer advice in relation to this for those children on their caseload – schools can also secure manual handling training.

- Equipment and resources monitored and altered/adapted as required as the child / young person grows, develops and matures. This will involve external agencies as well as school staff.

- Close supervision to address safety and access in PE, during free-flow indoor/outdoor periods and unstructured periods of the day, e.g. break times.

- Support to address self-care needs with a focus on privacy, dignity and promoting independence.

- A manual handling plan should be in place with appropriately trained staff to implement this. This would normally be developed with specialist support.

- School undertakes risk assessments as required, e.g. for emergency evacuation.

Access to the curriculum

- Significant modification and/or differentiation of some/many aspects of the curriculum.

- Physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy advice integrated into the child or young person’s personal programme, with specific time allocated to this as required.

- Teaching delivered through a highly individualised approach with planned opportunities to access specific individual programmes of support.

- Planned opportunities created for peer to peer interaction if needed.

- Progress monitored using highly structured methods.

- Support to develop independent living skills through access to targeted interventions when needed.

- Planned time to engage in community activity.

- Additional adults support the young person individually, under the direction of the teacher to:

- Access regular, individual support

- Encourage independence

- Create frequent opportunities for peer to peer interaction

- Monitor the progress of the young person using structured methods

- Access programmes of support as advised by the paediatric therapy team.

- Pace of teaching takes account of possible fatigue and any frustration experienced.